Aimed at children, the phenomenon is far more subversive than its defenders claim.

Christopher F. Rufo Autumn 2022 The Social Order Education

Drag Queen Story Hour—in which performers in drag read books to kids in libraries, schools, and bookstores—has become a cultural flashpoint. The political Right has denounced these performances as sexual transgressions against children, while the political Left has defended them as an expression of LGBTQ pride. The intellectual debate has even spilled into real-world conflict: right-wing militants affiliated with the Proud Boys and the Three Percenters have staged protests against drag events for children, while their counterparts in the left-wing Antifa movement have responded with offers to serve as a protection force for the drag queens.

Families with children find themselves caught in the middle. Drag Queen Story Hour pitches itself as a family-friendly event to promote reading, tolerance, and inclusion. “In spaces like this,” the organization’s website reads, “kids are able to see people who defy rigid gender restrictions and imagine a world where everyone can be their authentic selves.” But many parents, even if reluctant to say it publicly, have an instinctual distrust of adult men in women’s clothing dancing and exploring sexual themes with their children.

These concerns are justified. But to mount an effective opposition, one must first understand the sexual politics behind the glitter, sequins, and heels. This requires a working knowledge of an extensive history, from the origin of the first “queen of drag” in the late nineteenth century to the development of academic queer theory, which provides the intellectual foundation for the modern drag-for-kids movement.

The drag queen might appear as a comic figure, but he carries an utterly serious message: the deconstruction of sex, the reconstruction of child sexuality, and the subversion of middle-class family life. The ideology that drives this movement was born in the sex dungeons of San Francisco and incubated in the academy. It is now being transmitted, with official state support, in a number of public libraries and schools across the United States. By excavating the foundations of this ideology and sifting through the literature of its activists, parents and citizens can finally understand the new sexual politics and formulate a strategy for resisting it.

Start with queer theory, the academic discipline born in 1984 with the publication of Gayle S. Rubin’s essay “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” Beginning in the late 1970s, Rubin, a lesbian writer and activist, had immersed herself in the subcultures of leather, bondage, orgies, fisting, and sado-masochism in San Francisco, migrating through an ephemeral network of BDSM (bondage, domination, sadomasochism) clubs, literary societies, and New Age spiritualist gatherings. In “Thinking Sex,” Rubin sought to reconcile her experiences in the sexual underworld with the broader forces of American society. Following the work of the French theorist Michel Foucault, Rubin sought to expose the power dynamics that shaped and repressed human sexual experience.

“Modern Western societies appraise sex acts according to a hierarchical system of sexual value,” Rubin wrote. “Marital, reproductive heterosexuals are alone at the top erotic pyramid. Clamouring below are unmarried monogamous heterosexuals in couples, followed by most other heterosexuals. . . . Stable, long-term lesbian and gay male couples are verging on respectability, but bar dykes and promiscuous gay men are hovering just above the groups at the very bottom of the pyramid. The most despised sexual castes currently include transsexuals, transvestites, fetishists, sadomasochists, sex workers such as prostitutes and porn models, and the lowliest of all, those whose eroticism transgresses generational boundaries.”

Rubin’s project—and, by extension, that of queer theory—was to interrogate, deconstruct, and subvert this sexual hierarchy and usher in a world beyond limits, much like the one she had experienced in San Francisco. The key mechanism for achieving this turn was the thesis of social construction. “The new scholarship on sexual behaviour has given sex a history and created a constructivist alternative to” the view that sex is a natural and pre-political phenomenon, Rubin wrote. “Underlying this body of work is an assumption that sexuality is constituted in society and history, not biologically ordained. This does not mean the biological capacities are not prerequisites for human sexuality. It does mean that human sexuality is not comprehensible in purely biological terms.” In other words, traditional conceptions of sex, regarding it as a natural behavior that reflects an unchanging order, are pure mythology, designed to rationalize and justify systems of oppression. For Rubin and later queer theorists, sex and gender were infinitely malleable. There was nothing permanent about human sexuality, which was, after all, “political.” Through a revolution of values, they believed, the sexual hierarchy could be torn down and rebuilt in their image.

There was some reason to believe that Rubin might be right. The sexual revolution had been conquering territory for two decades: the birth-control pill, the liberalization of laws surrounding marriage and abortion, the intellectual movements of feminism and sex liberation, the culture that had emerged around Playboy magazine. By 1984, as Rubin acknowledged, stable homosexual couples had achieved a certain amount of respectability in society. But Rubin, the queer theorists, and the fetishists of the BDSM subculture wanted more. They believed that they were on the cusp of fundamentally transforming sexual norms. “There [are] historical periods in which sexuality is more sharply contested and more overtly politicized,” Rubin wrote. “In such periods, the domain of erotic life is, in effect, renegotiated.” And, following the practice of any good negotiator, they laid out their theory of the case and their maximum demands. As Rubin explained: “A radical theory of sex must identify, describe, explain, and denounce erotic injustice and sexual oppression. Such a theory needs refined conceptual tools which can grasp the subject and hold it in view. It must build rich descriptions of sexuality as it exists in society and history. It requires a convincing critical language that can convey the barbarity of sexual persecution.” Once the ground is softened and the conventions are demystified, the sexual revolutionaries could do the work of rehabilitating the figures at the bottom of the hierarchy—“transsexuals, transvestites, fetishists, sadomasochists, sex workers.”

Where does this process end? At its logical conclusion: the abolition of restrictions on the behavior at the bottom end of the moral spectrum—pedophilia. Though she uses euphemisms such as “boylovers” and “men who love underaged youth,” Rubin makes her case clearly and emph

atically. In long passages throughout “Thinking Sex,” Rubin denounces fears of child sex abuse as “erotic hysteria,” rails against anti–child pornography laws, and argues for legalizing and normalizing the behavior of “those whose eroticism transgresses generational boundaries.” These men are not deviants, but victims, in Rubin’s telling. “Like communists and homosexuals in the 1950s, boylovers are so stigmatized that it is difficult to find defenders for their civil liberties, let alone for their erotic orientation,” she explains. “Consequently, the police have feasted on them. Local police, the FBI, and watchdog postal inspectors have joined to build a huge apparatus whose sole aim is to wipe out the community of men who love underaged youth. In twenty years or so, when some of the smoke has cleared, it will be much easier to show that these men have been the victims of a savage and undeserved witch hunt.” Rubin wrote fondly of those primitive hunter-gatherer tribes in New Guinea in which “boy-love” was practiced freely.

Such positions are hardly idiosyncratic within the discipline of queer theory. The father figure of the ideology, Foucault, whom Rubin relies upon for her philosophical grounding, was a notorious sadomasochist who once joined scores of other prominent intellectuals to sign a petition to legalize adult–child sexual relationships in France. Like Rubin, Foucault haunted the underground sex scene in the Western capitals and reveled in transgressive sexuality. “It could be that the child, with his own sexuality, may have desired that adult, he may even have consented, he may even have made the first moves,” Foucault once told an interviewer on the question of sex between adults and minors. “And to assume that a child is incapable of explaining what happened and was incapable of giving his consent are two abuses that are intolerable, quite unacceptable.”

Rubin’s American compatriots made the same argument even more explicitly. Longtime Rubin collaborator Pat Califia, who would later become a transgender man, claimed that American society had turned pedophiles into “the new communists, the new niggers, the new witches.” For Califia, age-of-consent laws, religious sexual mores, and families who police the sexuality of their children represented a thousand-pound bulwark against sexual freedom. “You can’t liberate children and adolescents without disrupting the entire hierarchy of adult power and coercion and challenging the hegemony of antisex fundamentalist religious values,” she lamented. All of it—the family, the law, the religion, the culture—was a vector of oppression, and all of it had to go.

The second prerequisite for understanding Drag Queen Story Hour is to understand the historical development of the art of drag. It begins with a freed slave named William Dorsey Swann, who dressed in elaborate silk and satin women’s costumes, called himself the “queen of drag,” and organized sexually charged soirées in his home in Washington, D.C. Over the course of his life, Swann was convicted of petty larceny—he had stolen books from a library and dinnerware from a private residence—and then, in 1896, was charged with “keeping a disorderly house,” a euphemism for running a brothel, and sentenced to 300 days in jail. From the viewpoint of modern sexual politics, the story has all the elements of the perfect left-wing archetype: Swann was a man who liberated himself from chattel slavery and then from a repressive sexual culture, despite the best efforts of the oppressors, the puritans, and the police.

Drag became explicitly political seven decades later, during the Stonewall riots of 1969, in which patrons of a gay bar in New York City rioted against police and began a wave of gay and lesbian political activism. As writer Daniel Harris explained in the counterculture journal Salmagundi, traditional drag performances from William Dorsey Swann until the mid-1960s were sensual experiences, “an innocuous camp pastime,” but with the onset of the sexual revolution, they became forms of resistance and revolution. “After the 1960s,” Harris wrote, “ideology [tightened] its grip on the aesthetic of drag when gay men began to use their costumes to reevaluate the whole concept of normality and thus carry out a crucial part of the cross-dresser’s agenda: revenge.” Drag performers increasingly saw their vocation as political and started street organizations such as Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries in order to join the wave of activism rising through their communities in New York, San Francisco, and other hubs.

Suddenly, drag was not a private performance but a statement of public rebellion. The queens began using costume and performance to mock the fashion, manners, and mores of Middle America. In time, the need to shock required the performers to push the limits. “Men now wear such sexually explicit outfits as ball gowns with prosthetic breasts sewn on to the outside of the dresses, black nighties with gigantic strap-on dildos, and transparent vinyl mini-skirts that reveal lacy panties with strategic rips and telltale stains suggestive of deflowerment,” Harris noted. “The less drag is meant to allure, the bawdier it becomes, with men openly massaging their breasts, squeezing the bulges of their g-strings, sticking out their asses and tongues like porn stars in heat, and lying spread-eagle on their backs on parade routes with their helium heels flung into the air and their virginal prom dresses thrown over their heads.”

“The goal of drag, following Butler and Rubin, is to obliterate conceptions of gender through performativity.”

The next critical turn occurred in 1990, with the publication of Gender Trouble, by the queer theorist Judith Butler. Gender Trouble was a bombshell: it elevated the discourse around queer sexuality from the blunt rhetoric of Gayle Rubin to a realm of highly abstract, and sometimes impenetrable, intellectualism. Butler’s essential contribution was twofold: first, she saturated queer theory with postmodernism; second, she provided a theory of social change, based on the concept of “performativity,” which offered a more sophisticated conceptual ground than simple carnal transgression. Gender Trouble’s basic argument is that Western society has created a regime of “compulsory heterosexuality and phallogocentrism,” which has sought to enforce a singular, unitary notion of “sex” that crushes and obscures the true complexity and variation of biological sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, and human desire. Butler argues that even the word “woman,” though it relates to a biological reality, is a social construction and cannot be defined with any stable meaning or categorization. There is nothing essential about “man,” “woman,” or “sex”: they are all created and re-created through historically contingent human culture; or, as Butler puts it, they are all defined through their performance, which can change, shift, and adapt across time and space.

Butler’s theory of social change is that once the premise is established that gender is malleable and used as an instrument of power, currently in favor of “heterosexual normativity,” then the work of social reconstruction can begin. And the drag queen embodies Butler’s theory of gender deconstruction. “The performance of drag plays upon the distinction between the anatomy of the performer and the gender that is being performed. But we are actually in the presence of three contingent dimensions of significant corporeality: anatomical sex, gender identity, and gender performance,” Butler writes. “When such categories come into question, the reality of gender is also put into crisis: it becomes unclear how to distinguish the real from the unreal. And this is the occasion in which we come to understand that what we take to be ‘real,’ what we invoke as the naturalized knowledge of gender is, in fact, a changeable and revisable reality. Call it subversive or call it something else. Although this insight does not in itself constitute a political revolution, no political revolution is possible without a radical shift in one’s notion of the possible and the real.”

By the 2000s, the performance of drag had absorbed all these elements—the social-justice origin story of William Dorsey Swann, the carnal shock-and-awe of Gayle Rubin, the ethereal postmodernism of Judith Butler—and brought them together onto the stage. The queer theorist Sarah Hankins, who performed extensive field research in drag bars in the Northeast, captured the spirit of this subculture and its ideology in a study for the academic journal Signs. Drawing on the work of Rubin and Butler, Hankins describes three genres of drag—straight-ahead, burlesque, and genderfuck—that range from stripteases and lap dances to simulations of necrophilia, bestiality, and race fetishism. Hankins describes the world of drag as a “sociosexual economy,” in which the members of “que

erdom” can titillate, gratify, and reward one another with cash tips and money exchanges. “As an audience member, I have always experienced the tip exchange as payment for sexual gratification,” Hankins writes. “And I am aware that by holding up dollar bills, I can satisfy my arousal, at least partially: I can bring performers’ bodies close to mine and induce them to touch me or to let me touch them.” Or, as one of her research subjects, the drag queen Katya Zamolodchikova, puts it: “I’m literally out there peddling my pussy for dollar bills.”

The goal of drag, following the themes of Butler and Rubin, is to obliterate stable conceptions of gender through performativity and to rehabilitate the bottom of the sexual hierarchy through the elevation of the marginal. “The act of paying a dominant/domineering woman, a male supplicant, a hapless wage slave, or a boy allows the audience member to temporarily embody one or more of a number of ‘bad/unnatural’ social positions, for instance the pedophile, the closeted gay chickenhawk, the predatory female cougar, the sugar daddy or momma, even the sexualized youth/child themselves,” Hankins writes. And the discipline of “genderfuck” takes it a step even beyond adult–child sex. As Hankins describes, this style of performance “foregrounds tropes of primitivism and degeneracy as tools of protest and liberation” and seeks to subvert taboos against “pedophilia, necrophilia, erotic object fetishism, and human–animal sex.” These performances constitute the end of the line: the culmination of more than a century’s work, from the silk-and-satin drag balls to the hyper-cerebral politics of deconstruction to the annihilation of traditional notions of sex.

The final turn in the story of drag is, in some ways, the most surprising. As the dark side of drag pushed transgression to the limits, another faction began moving from the margins to the mainstream. Some drag queens—most notably, the drag performer RuPaul—toned down the routines, pushed the ideology deep into the background, and presented drag as good old-fashioned, glamorous American fun. Television producers packaged this new form of drag as reality programming, softening the image of the drag queen and assimilating the genre into mass media and consumer culture.

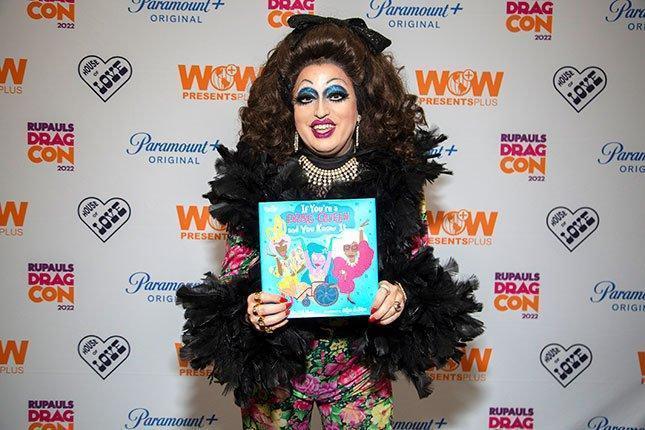

This provided an opportunity. As the queer theorists’ vanguard intellectual project was running aground on incest and bestiality fantasies, the most enterprising among them took a different tack: using the commercialization of drag and the goodwill associated with the gay and lesbian rights movement as a means of transforming drag performances into “family-friendly” events that could transmit a simplified version of queer theory to children. The key figure in this transition was a “genderqueer” college professor and drag queen named Harris Kornstein—stage name Lil Miss Hot Mess—who hosted some of the original readings in public libraries and wrote the children’s book The Hips on the Drag Queen Go Swish, Swish, Swish. Kornstein sits on the board of Drag Queen Story Hour, the nonprofit organization that was founded by Michelle Tea in 2015 to promote “family-friendly” drag performances and has since expanded to 40 local chapters that have organized hundreds of performances across the United States.

Kornstein also published the manifesto for the movement, “Drag Pedagogy: The Playful Practice of Queer Imagination in Early Childhood,” with coauthor Harper Keenan, a female-to-male transgender queer theorist at the University of British Columbia. With citations to Foucault and Butler, the essay begins by applying queer theory’s basic premise of social constructivism and heteronormativity to the education system. “The professional vision of educators is often shaped to reproduce the state’s normative vision of its ideal citizenry. In effect, schooling functions as a way to straighten the child into a kind of captive alignment with the current parameters of that vision,” Kornstein and Keenan write. “To state it plainly, within the historical context of the USA and Western Europe, the institutional management of gender has been used as a way of maintaining racist and capitalist modes of (re)production.”

To disrupt this dynamic, the authors propose a new teaching method, “drag pedagogy,” as a way of stimulating the “queer imagination,” teaching kids “how to live queerly,” and “bringing queer ways of knowing and being into the education of young children.” As Kornstein and Keenan explain, this is an intellectual and political project that requires drag queens and activists to work toward undermining traditional notions of sexuality, replacing the biological family with the ideological family, and arousing transgressive sexual desires in young children. “Building in part from queer theory and trans studies, queer and trans pedagogies seek to actively destabilize the normative function of schooling through transformative education,” they write. “This is a fundamentally different orientation than movements towards the inclusion or assimilation of LGBT people into the existing structures of school and society.”

For the drag pedagogists, the traditional life path—growing up, getting married, working 40 hours a week, and raising a family—is an oppressive bourgeois norm that must be deconstructed and subverted. As the drag queens take the stage in their sexually suggestive costumes, Kornstein and Keenan argue, their task is to disrupt the “binary between womanhood and manhood,” seed the room with “gender-transgressive themes,” and break the “reproductive futurity” of the “nuclear family” and the “sexually monogamous marriage”—all of which are considered mechanisms of heterosexual, capitalist oppression. The books selected in many Drag Queen Story Hour performances—Cinderelliot, If You’re a Drag Queen and You Know It, The Gender Wheel, Bye Bye, Binary, and They, She, He, Easy as ABC—promote this basic narrative. Though Drag Queen Story Hour events are often billed as “family-friendly,” Kornstein and Keenan explain that this is a form of code: “It may be that DQSH is ‘family friendly,’ in the sense that it is accessible and inviting to families with children, but it is less a sanitizing force than it is a preparatory introduction to alternate modes of kinship. Here, DQSH is ‘family friendly’ in the sense of ‘family’ as an old-school queer code to identify and connect with other queers on the street.” That is, the goal is not to reinforce the biological family but to facilitate the child’s transition into the ideological family.

After the norms of gender, sexuality, marriage, and family are called into question, the drag queen can begin replacing this system of values with “queer ways of knowing and being.” Kornstein and Keenan make no bones about it: the purpose of what they call drag pedagogy, or the “pedagogy of desire,” is about reformulating children’s relationship with sex, sexuality, and eroticism. They describe drag as a “site of queer pleasure” that promises to “turn rejection into desire” and “[transform] the labour of performance into the pleasure of participation,” and DQSH as offering a “queer relationality” between adult and child. They litter their paper with sexualized language and double entendres, blurring the lines between adult sexuality and childhood innocence. In fact, as the queer pedagogist Hannah Dyer has written, queer pedagogy and, by extension, drag pedagogy seek to expose the very concept of “childhood innocence” as an oppressive heteropatriarchal illusion. “Applying queer methods of analysis to studies of childhood can help to queer the rhetoric of innocence that constrains all children and help to refuse attempts to calculate the child’s future before it has the opportunity to explore desire,” Dyer writes.

The purpose, then, is to subvert the system of heteronormativity, which includes childhood innocence, and reengineer childhood sexuality from the ground up. And drag performances provide a visual, symbolic, and erotic method for achieving this. Kornstein and Keenan’s language of the discipline—“pleasure,” “desire,” “bodies,” “girls,” “boys,” “glitter,” “sequins,” “wigs,” and “heels”—gives it away.

Of course, the organizers of Drag Queen Story Hour understand that they must manage their public image to continue enjoying access to public libraries and public schools. They have learned how to speak in code to NGOs and to appease the anxieties of parents, while subtly promoting the ideology of queer theory to children. While many of Drag Queen Story Hour’s defenders claim that these programs are designed to foster LGBTQ “acceptance” and “inclusion,” Kornstein and Keenan explicitly dismiss those objectives as mere “marketing language” that provides cover for their real agenda. “Though DQSH publicly positions its impact in ‘help[ing] children develop empathy, learn about gender diversity and difference, and tap into their own creativity,’ we argue that its contributions can run deeper than morals and role models,” they write. “As an organization, DQSH may be incentivized to recite lines about alignment with curricular standards and social-emotional learning in order to be legible within public education and philanthropic institutions. Drag itself ultimately does not take these utilitarian aims too seriously (but it is quite good at looking the part when necessary).” In other words, as a movement, Drag Queen Story Hour has learned the dance of operating a cash-flow-positive activist organization, winning government contracts, and securing access to audiences, while providing a plausible rhetorical defense against parents who might question the wisdom of adult men creating “site[s] of queer pleasure” with their children.

This gambit has been remarkably successful. Drag Queen Story Hour began with voluntary programs at public libraries, which are required by law to provide equal access to organizations regardless of political affiliation or ideology. But within a few years, those state-neutral events have turned into state-subsidized drag performances for children. The New York City Council and New York Public Library have provided taxpayer funding directly to the Drag Queen Story Hour nonprofit, sparking a trend of state-subsidized drag readings, dances, and performances across the country. Next, the New York City Public Schools, with more than $200,000 in funding from the municipal government, began hosting dozens of drag performances in elementary, middle, and high sch

ools in all five boroughs. Other political figures seem to want to go even further. The attorney general of Michigan has called for a “drag queen for every school.” California state senator Scott Wiener has suggested in a tweet that he might propose legislation to offer “Drag Queen 101 as part of the K–12 curriculum” and mandate that students attend Drag Queen Story Time as a way to “satisfy the requirement.” Both might have said this tongue in cheek—but in any case, these things have a way of going from joke to reality at the speed of light.

“New York City began hosting dozens of drag performances in public schools in all five boroughs.”

Though the spread of sexually charged drag performances has an aura of inevitability, one should keep in mind that transgressive ideologies always contain the seeds of their own destruction.

As the movement behind drag shows for children has gained notoriety and expanded its reach, some drag performers have let the mask slip: in Minneapolis, a drag queen in heels and a pink miniskirt spread his legs open in front of children; in Portland, a large male transvestite allowed toddlers to climb on top of him, grab at his fake breasts, and press themselves against his body; and in England, a drag queen taught a group of preschoolers how to perform a sexually suggestive dance.

Scenes from drag events hosted across the United States in bars, clubs, and outdoor festivals have been even more shocking and disturbing: in Miami, a man with enormous fake breasts and dollar bills stuffed into his G-string grabs the hand of a preschool-aged girl and struts her in front of the crowd; in Washington, D.C., a drag queen wearing leather and chains teaches a young child how to dance for cash tips; in Dallas, hulking male figures with makeup smeared across their faces strip down to undergarments, simulate a female orgasm, and perform lap dances on members of a roaring audience of adults and children. Newspaper headlines have also announced abuses: “Tucson High School Counselor Behind Teen Drag Show Arrested for Relationship with Minor”; “Houston Public Library Admits Registered Child Sex Offender Read to Kids in Drag Queen Storytime”; “Drag Queen Charged with 25 Counts of Felony Child Sexual Abuse Material Possession”; “Second ‘Drag Queen Story Hour’ Reader in Houston Exposed as Convicted Child Sex Offender”; “Drag Queen Story Hour Activist Arrested for Child Porn, Still Living with His Adopted Kids.”

Advocates of Drag Queen Story Hour might reply that these are outlier cases and that many of the child-oriented events feature drag queens reading books and talking about gender, not engaging in sexualized performances. But the spirit of drag is predicated on the transgressive sexual element and the ideology of queer theory, which cannot be erased by switching the context and softening the language. The philosophical and political project of queer theory has always been to dethrone traditional heterosexual culture and elevate what Rubin called the “sexual caste” at the bottom of the hierarchy: the transsexual, the transvestite, the fetishist, the sadomasochist, the prostitute, the porn star, and the pedophile. Drag Queen Story Hour can attempt to sanitize the routines and run criminal background checks on its performers, but the subculture of queer theory will always attract men who want to follow the ideology to its conclusions.

When parents, voters, and political leaders understand the true nature of Drag Queen Story Hour and the ideology that drives it, they will work quickly to restore the limits that have been temporarily—and recklessly—abandoned. They will draw a bright line between adult sexuality and childhood innocence, and send the perversions of “genderfuck,” “primitivism,” and “degeneracy” back to the margins, where they belong.

Christopher F. Rufo is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal.

Top Photo: Drag queens read to children at a public library in Chelsea, Massachusetts. (ERIN CLARK/THE BOSTON GLOBE/GETTY IMAGES)